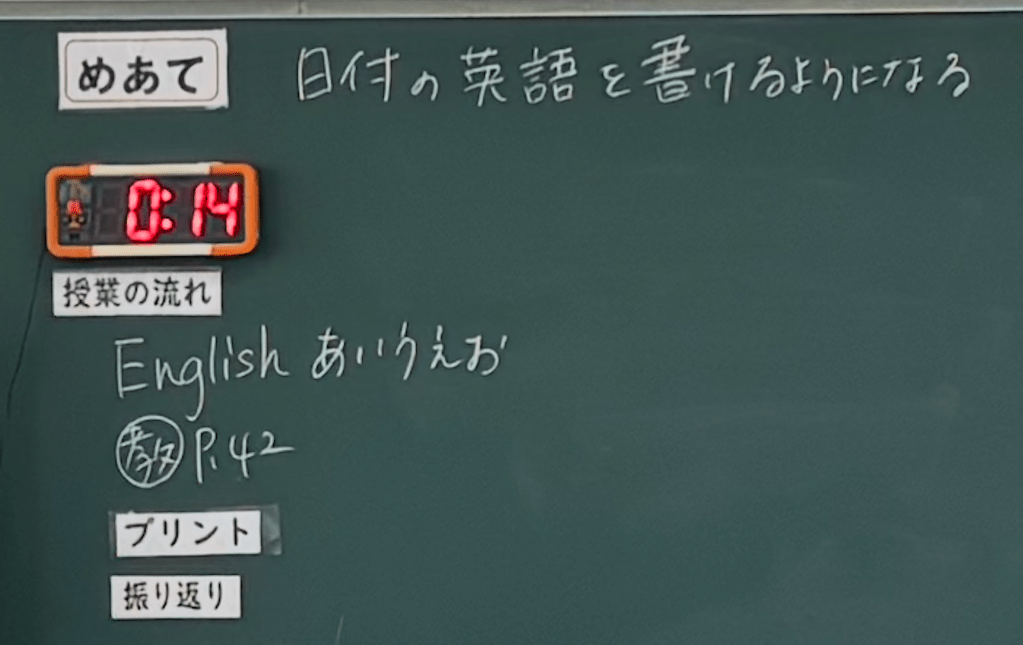

Naoko Sensei puts a digital countdown timer on the board. Sets it to 40 seconds. All pupils stand up: it is time to practice, in pairs, the months in English. One of the students says 2月, the other one responds in English: February. A boy says 4月, and after some hesitation, a girl says April. They test each other, they laugh, they speak together…It is also one of those rare moments when I do not really know if they can hear each other, when there is at least some chaos, a very very rare moment, a move away from the choral repetition. They have 40 seconds. Then the alarm goes off, they all stop speaking and sit down. A few minutes later, the teacher sets the timer again to 40 seconds. The kids open page 24 in their course book. They read the words in 40 seconds. And then the alarm goes off. Loud and clear. Time is up. A few minutes after that the timer is set to 20 seconds. The teacher says February. They have 20 seconds to write it down, in their book. Then March. Then April. 20 seconds each. Then the alarm goes off. 20 seconds is all they have. They then move on to practicing “ordinal numbers”. First, second, third…The teacher accidentally sets the timer to 2 seconds this time. They all laugh together. They know that it is too little time to do anything. They are all (made) aware of the amount of time they have. They all hear an alarm when the time is up, all thanks to a countdown timer. The loud sound tells the students that their little time for a given activity is over.

Do the students like it? Maybe not always. One of the kids walks towards the board to get something from the teacher’s desk, and then the alarm goes off, loud and unexpected for him. He closes his ears with his hands, and he closes his eyes. The irritation is visible. It looks like he does not like the noise of the alarm, at least at that moment. But digital countdown timers and their alarms are obviously what we have in many Japanese junior high schools, as I was told by my friend Mika and Naoko Sensei after the lessons I observed. Every day, in each lesson, kids orient to timers and their sounds – they look at it, they hear it, they act on it, they laugh at it. If there is anything that they all have, it is time. But how much of it? How does each kid experience the 40 seconds they are given for a short activity? How does the teacher experience and manage it? What would have happened without a timer? Without knowing the exact seconds they have before moving to another activity? No matter how short or long time is, it is obvious that what each kid makes out of it and how each teacher experiences it will be relatively different each time. I will not discuss here whether or how these timers obstruct or construct learning opportunities. It is obvious why they are there. We do not know in reality the relationship between these timers and learning1. But if there is one reality that we cannot escape from, it is the fact that time is relative no matter how we want to set boundaries around it with countdown timers in schools, digital calendars in our smart(!) phones and computers, and the number of days, weeks, and months. This is exactly how I have perceived time during the first week of my “minigration2” (i.e., mini-immigration) to Japan.

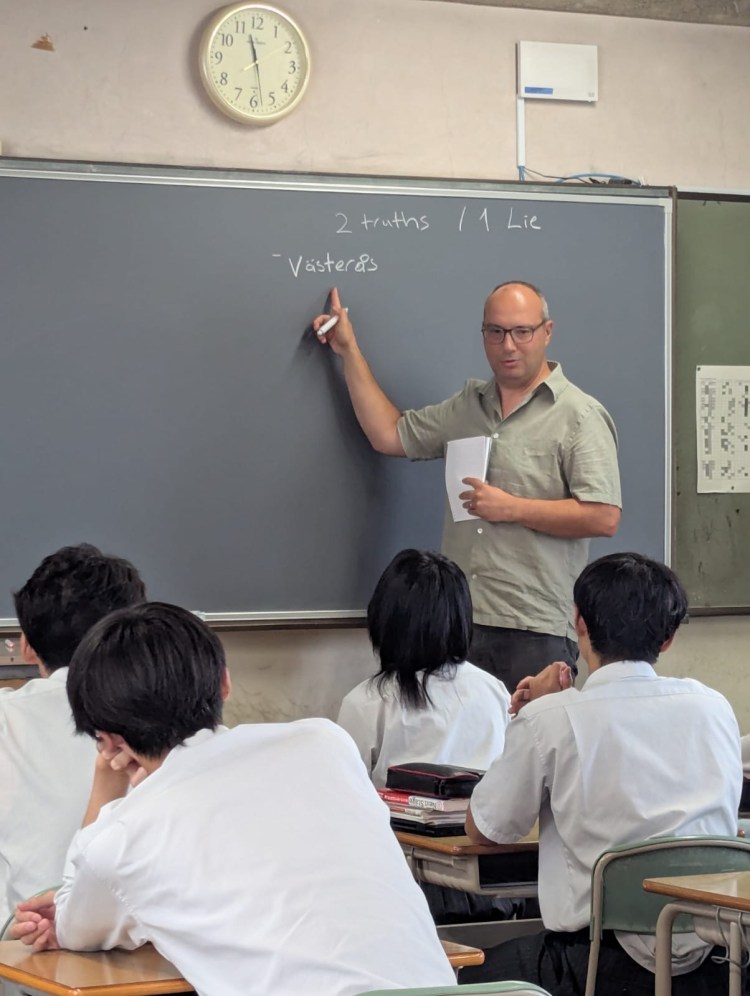

I am a seasoned immigrant. I moved and adapted to cities like Newcastle, Luxembourg, Västerås where I spent years of my life. My minigration to Kyoto has been a different story though in terms of how I perceive time and space. I have only been here for less than two weeks3, yet it feels like the new experiences and things I have encountered exceeds what I had seen during the first weeks in any other city I’ve lived in (and I still have more than four weeks to go!). Wherever you look, you see something that is totally new to you – the food you taste is not just amazing, but it also takes you to a journey of new experiences mixed with old tastes. When I spent time in Japanese classrooms, I took a spiritual journey which was a mixture of my childhood memories in classrooms in Gemlik4 and all the cultural fingerprints of Japanese culture embedded in the learning activities. Each and every moment I spent in the Japanese classrooms as an observer (and very briefly as a guest teacher) triggered reflections on the spot – it was almost like watching a film in small motion, noticing tons of things in what students and teachers do while at the same time, in the background, recalling classroom memories from my childhood, and then starting to compare, at the very moment, things that I observed in Swedish or Luxembourgish classrooms to what I see in Japan. All at the same time. It was full of life, and at the same time felt like a dream in consciousness. I woke up when one Japanese pupil approached me right after the lesson (in which I also taught briefly) and asked my opinions on the differences between Swedish and Japanese classrooms. I was shocked at first but was pleasantly surprised. This is a question that I have been trying to answer with my colleague Mika Ishino and my student-teachers in Sweden who worked with Japanese student-teachers as part of a teacher education course. Yet, the question comes from a 15-year-old boy, who takes the courage to ask in English a very grown-up question. Smart, courageous, curious, kind. I tried to explain him in just a minute what I think and what I have observed then and over the years.

Where was I. A countdown timer with a built-in magnet helped me reflect on time. How much time do we have? What do we want to do with it? What can be done? In a classroom, in a new city, with the people you know and with those you encounter for the first time. Does it help us if we are reminded about time ‘all the time’, like the students in Japanese classrooms who see the countdown timer on regular basis? So much and so many can go into a limited amount of time. The quality of experience, not its quantity, will matter. Same goes for learning and teaching activities. But what to do as a teacher? How can we manage the limited time we have to create limitless meaningful experiences for our students and for ourselves? We still need to be aware of the limits of time, while also refraining from constantly thinking about the quantitative borders time creates. Embrace every second, observe each pupil, smell the atmosphere of the classroom. Try to see all the little details in the physical environment and in what students do with the time we give them. It is a little bit of being able to slow down, appreciate the imperfection5 in the state of events, and being in peace with that imperfection. How much time do we have? That we do not know.

織在猿人(Olcay Sert )

17-21 July 2025, Kyoto

1. Although I am not aware of any classroom research on countdown timers, Tim Greer published research that investigates students’ orientations to countdown timers in testing settings in Japan:

Greer, T. (2019). Closing up testing: Interactional orientation to a timer during a paired EFL proficiency test. In H. T. Nguyen & T. Malabarba (Eds.) Conversation Analytic Perspectives on English Language Learning, Teaching and Testing in Global Contexts (pp. 159-190). Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

2. I promise I will write a separate post on the concept of minigration.

3. When I started writing this post I was at the end of my first week.

4. I grew up in Gemlik, Bursa, where I completed my primary, secondary school education.

5. This idea of embracing is strongly tied to Wabi Sabi. Check this out for a good introduction:

Kempton, B. (2018). Wabi Sabi: Japanese wisdom for a perfectly imperfect life. Hachette UK.